Down the Mississippi #4

We’re at the pristine headwaters of the Mississippi in very far northern Minnesota. Why in the world would water quality be something we think about here? Two easy answers come to mind immediately: 1) We are at the source of one of the longest rivers and largest river systems in the world. Contamination that enters the river here stays with the river until it empties into the Gulf of Mexico … and then it becomes Gulf contamination instead of river contamination. 2) Minnesota’s native Ojibwe people rely on wild rice for their diet and livelihood; compromising the ecosystem could have dire consequences on centuries of living sustainably.

In the world of drinking water quality, the idea of treating wastewater and reintroducing it to water supply sources gets a lot of attention. “Potable reuse” some people call it. In moments of serious cynicism, some have called the practice “toilet-to-tap.” Such labeling has not helped the concept get a lot of traction. Astronauts have relied on it since humans have started spending time in space.

On Monday morning, I spent an hour or so at the Bemidji Wastewater Treatment Plant with Al Gorick, Bemidji, Minnesota’s Wastewater Superintendent. Al takes his job very seriously. Bemidji is the first town along the Mississippi to send its treated wastewater back into the river.

A few miles downstream, Grand Rapids is the first town to draw its drinking water from the river. Part of that drinking water used to be Bemidji’s wastewater. Those practices of drawing drinking water and releasing wastewater will continue through hundreds of cities between here and the Gulf of Mexico. If you consider the entire river system – the Missouri, the Ohio, the Illinois, the Des Moines, and all of the other rivers that feed the Mississippi – that practice will continue through thousands of cities, and perhaps tens of thousands. To the uninformed, the practice may sound gross, but it’s not. We know a lot about cleaning water, and nature is ridiculously resilient.

Bemidji is a college town with a permanent population of only 15,000. Its wastewater treatment plant is pretty vanilla: a capacity of two million gallons per day (but a daily load of only about one million gallons), and a process that entails “advanced activated sludge treatment” with “anaerobic digestion” of the solids. Here’s what that means: raw sewage flows into the plant. Solid stuff, like paper and debris, gets screened out, and the biological stuff settles to the bottom of big tanks. The solids then move to a digester where they get turned into fertilizer. The liquid moves to a secondary tank where the rest of the solid stuff settles out, and crystal clear water flows from the top. That clear water gets filtered through sand filters, disinfected with ultraviolet radiation, and then released directly into the northernmost waters of the Mississippi River. For all practical purposes, the water that flows from the plant into the river is of roughly the same quality as water from the tap … though Al claims that he would not drink it … and I am not 100% sure I would either.

These pictures show the full process: blackwater in, treatment, and clean, disinfected water out to the river.

For my money, the biggest problem with wastewater treatment has nothing to do with removing poop and the related germs. It has to do with all the stuff that is not regulated and is not easy to remove, like endocrine disrupters that come from pharmaceuticals and other chemicals. The drugs you flush down the sink, the junk you put on your face or skin and then wash down the drain, the drugs that you pee out because your body did not process them fully, and the crap that people put in their bodies to get high do not easily get removed from wastewater. But since no one really knows their toxicity levels or their long-term effects, and since they are not regulated, they must not really be a problem … even as their concentration increases between here and New Orleans. Right? Here’s a little light reading, if you are interested.

While water in the far north woods may seem to be pristine, it isn’t. As soon as it flows through the woods, it picks up contaminants, the most environmentally serious of which is phosphorous. Controlling the crap that goes into the river and managing water quality is as important in Minnesota as it is in New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. It is particularly important to Minnesota’s native Ojibwe.

The Ojibwe people have been harvesting wild rice in the waters of Minnesota’s north woods for millennia. Europeans have only been living in the north woods for a couple of centuries. We spent some of Monday with Jeff Harper, a fisheries expert who hosted us for a while on the reservation of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe.

The Ojibwe people have been harvesting wild rice in the waters of Minnesota’s north woods for millennia. Europeans have only been living in the north woods for a couple of centuries. We spent some of Monday with Jeff Harper, a fisheries expert who hosted us for a while on the reservation of the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe.

In a manner that might make Wall Street capitalists cringe, he respectfully described the tribe’s careful management of the wild rice crop and harvesting constraints. Each year, a tribal committee determines the length of the harvesting season and the length of the harvesting day based on the size of that year’s crop. Some days, harvesting can take place from sun up until sun down; on other days, harvesting may be limited to only a few hours. The Ojibwe recognize that some years will be plentiful and others sparse, and it is their responsibility to protect the crop, not for a single season, but forever.

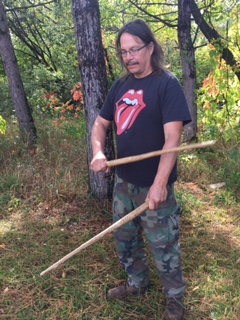

For a few weeks in late summer, Ojibwe canoe to the rice fields with the most primitive – and effective – of tools: “rice knockers.” They are nothing more than two straight, debarked sticks, usually made of white cedar, and often carved with simple hand grips. The rice knockers that Jeff gave to us have no hand grips; they are just simple, tapered, straight, lightweight pieces of wood.

For a few weeks in late summer, Ojibwe canoe to the rice fields with the most primitive – and effective – of tools: “rice knockers.” They are nothing more than two straight, debarked sticks, usually made of white cedar, and often carved with simple hand grips. The rice knockers that Jeff gave to us have no hand grips; they are just simple, tapered, straight, lightweight pieces of wood.

Two harvesters work together in a single canoe. The Ojibwe in the stern uses a long pole with a forked end to move the canoe slowly through the rice stalks. The harvester sits in front of the poler and uses the rice knockers to harvest the rice. With a smooth sweeping and knocking motion that does no damage to the rice plants, the harvesters slowly fill the canoe’s bow with rice. (This youtube video gives a taste of the harvesting process.)

Smooth and without damage, yes, but Jeff also described how some of his compadres dress for harvesting: with heavy clothing, eye protection, breathing protection, etc., etc. Smilingly, he noted that he sticks to the simple T-shirt look. The reason for the heavy garb is protective. The rice seeds can fly from the plant at some velocity. Heavy clothing tempers the sting. The eye protection ensures that none of the tiny pieces cause discomfort or get stuck in an eye. The clothing also protects against the critters that share the waterways with the rice: lots and lots of spiders and hellgrammites. A hellgrammite is the larva of the dobsonfly. If you have never encountered one, Google it. For a relatively harmless critter, they are about as ugly and fearsome looking as you can find, with sharp pincers growing from their head and guiding their way. (We fish for bass with them in Vermont; the Ojibwe co-exist with them while harvesting rice.) With a little carelessness, they can be pretty painful even if the related injury isn’t serious.

Jeff’s most colorful and poignant moment came when he described the mound of rice in the front of the canoe at the end of a day of harvesting. With all of the spiders and “worms” that accompany the rice into the canoe, the mound pulses with life. “They are part of nature too,” Jeff said. “They deserve their share just like we deserve ours.”

Jeff described the steps of processing the rice, which include heating the harvest, then crushing the chaff while “dancing” in moccasins inside a special barrel to separate the chaff from the grain, finally leaving nothing except beautiful rice grains.

We now have a suitcase full of bags of hand-harvested, organic wild rice from the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe. It is delicious, and will be our gift of choice along the route … until we run out and need to find another equally cool gift of choice.

© 2017 Kenneth Mirvis

Ken, I loved reading this entry, especially the wild rice harvesting bit. One of Anne’s fond memories was her experience harvesting wild rice (with permission of course) in northern Minnesota. You have chosen a wonderful gift to share down river.

LikeLike

We really have to figure out a way to control pharmaceuticals in our waste water. Better consumer education will help. Also, I think pharmacies should be required to have recycle bins for expired prescriptions.

I had no idea about the moccasin dance used to dehusk the wild rice, which isn’t related to rice. We get some wonderful Wild Rice from LaRonge in Northern Saskatchewan. The rice you got sounds great.

LikeLike