Our parents’ generation derived meaning from the Depression and World War II. For many years, I thought our generation would be defined by Viet Nam. It hasn’t. It has been and will continue to be defined by the Civil Rights Movement.

What a shift we have seen, from the Jim Crow south with its unabashed racism to a black president. We are now at the cusp of 2016. Despite how far society has come, there is still so much further to go. I cannot yet really imagine a “post-racial” America.

Having grown up in Atlanta and gone to college in New Orleans in the last four years of the 1960s – before the completion of the Interstates – my route took me through Selma on US 80 and across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. I have no clue how many times I have driven across the bridge. But I never stopped in Selma. It scared me.

I knew the bridge was important. I knew the history of Bloody Sunday and the march from Selma to Montgomery that led to the National Voting Rights Act. Like many bright undergraduates, I knew it in my head, but I knew nothing about it in my heart and soul. That knowledge has taken me a lifetime to begin to acquire.

As Rebecca and I planned our “Transition Tour” with its obligatory stops in Atlanta and New Orleans, spending time in Selma became equally important. We needed to walk across the bridge, following in the footsteps of some of America’s most important heroes.

Interestingly, I have almost-personal connections with four of the march’s most important leaders. My parents met Martin Luther King, Jr.; many of the people I knew from The Temple in Atlanta, especially our Rabbi, Jack Rothschild, knew him personally and closely. In the summer of 1970, I spent an afternoon in the rec room of the Ebenezer Baptist Church with Daddy King when I escorted a church choir group from Greensboro, NC as a Gray Line tour driver. I worked on Andrew Young’s campaign when he first ran for Congress in 1970, stuffing envelopes and driving voters to the polls. He once commented to my mother that “I was a fine young man,” one of those moments that becomes a lifelong source of pride. Many of my political friends from Atlanta have come to know John Lewis. And I recently learned that my lifelong friend Alan Begner, an attorney in Atlanta, represented Hosea Williams for 18 years until his death in 2000.

The walk was far more emotional than I could have anticipated. That emotion was compounded by some of the poverty conditions we drove through on our way to Selma. From Atlanta, we took I-85 about 25 miles to Newnan, and from there, we drove only state and county highways to Selma. We saw some of the most impressive clusters of “manufactured homes” I have ever seen, and we left Selma heading south with a tornado watch to our west. A community of single-wide trailers in a flat, unprotected Alabama field during a tornado watch leaves a deep ache in the pit of my stomach. We have come so far, but we still have so far to go.

The National Voting Rights Museum fills an old building at the southwest end of the bridge. It’s a tired-looking place with no real outstanding features, privately run, and apparently chronically under-funded. It was closed for the week between Christmas and New Year, so sadly we couldn’t visit. Its only visible outstanding feature was the storage building between it and the river. Eight murals on eight garage doors told a powerful story that began with “Education is the Key to Control our Destiny” and ended with “Hands that picked cotton picked a President!”

My experience of driving through Selma almost 50 years ago was one of fear of the police and the good-ole-boys. I was an uppity city Jew-boy with long hair and a beard going to college in New Orleans. They’d go out of their way to find a way to bust me. Fortunately, they never did.

When a Selma police car pulled behind us as we were trying to find an open restaurant, my heart went into my throat. I prepared for the worst. As we approached a traffic light, the police car pulled alongside us, a young black cop at the wheel. We rolled down the window and asked if he could recommend a restaurant. We stayed at that light through three cycles as he thought of places we could try, explained what they were like, and gave us directions to each.

When we arrived at a small bustling family restaurant we were pleasantly surprised. We fully expected a totally integrated establishment. What we did not expect was how many of the tables had black and white diners eating together, many of them apparently family; all of them obviously good friends. The arc of justice is indeed bending.

Selma’s two lagniappes proved to be our lodging and our breakfast. Built in 1837, the St. James Hotel is reputedly the most haunted site in Alabama. We didn’t get to meet any of it “haints,” but we did bask in its splendid luxury, even if only overnight, and even if the beds were a tad on the soft side. We’d stay in places like that every night if we could find them … especially if they had a staff like the St. James. Breakfast at the Downtowner on Selma Street approached southern perfection: grits, fluffy biscuit, well-cooked egg, amazing bacon and sausage, plenty of hot coffee, and world-class conversations to eavesdrop. (The most important takeaway: my deep southern accent ain’t half bad!)

After breakfast, I visited the newspaper office for a quick chit-chat while Rebecca returned to the hotel to shower. A half-hour or so later, I too returned to the hotel. Rebecca had not made it past the lobby, where she stood grinning and jawboning with the hotel manager, Annette.

Annette, I really hope you enjoy reading this blog, and we cannot wait to see you and stay at the St. James again for the 2017 Jubilee and march from Selma to Montgomery!!

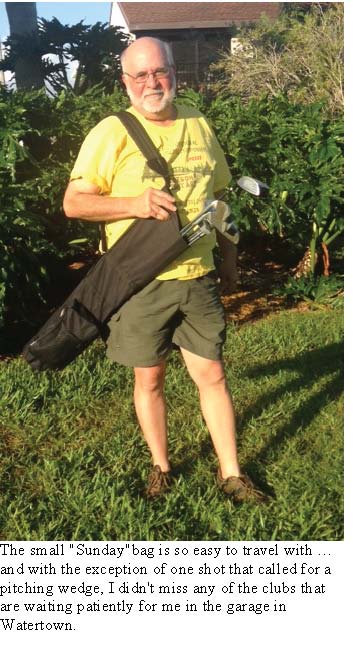

My brother Joe calls golf “urban fishing.” I agree wholeheartedly. You don’t go fishing to catch fish. You go fishing to hang out on the water in a state of totally chill relaxation, taking in nature and forgetting about reality. Catching fish is a bonus … a “lagniappe” in the language of south Louisiana.

My brother Joe calls golf “urban fishing.” I agree wholeheartedly. You don’t go fishing to catch fish. You go fishing to hang out on the water in a state of totally chill relaxation, taking in nature and forgetting about reality. Catching fish is a bonus … a “lagniappe” in the language of south Louisiana. The title is misleading. Miss Donna has not cut my mother’s hair for fifty years. But she has been involved with my mother’s haircutting for that long. Miss Donna was 22 and my mother 45. At the time, Mom had her hair cut by a man at the salon where Donna worked. He was chronically late. Mom HATES late. One day when her appointment time passed and he still wasn’t there, Miss Donna said to her, “Let’s just get it done.” By the time he arrived, Mom had a new hairdresser. He was history.

The title is misleading. Miss Donna has not cut my mother’s hair for fifty years. But she has been involved with my mother’s haircutting for that long. Miss Donna was 22 and my mother 45. At the time, Mom had her hair cut by a man at the salon where Donna worked. He was chronically late. Mom HATES late. One day when her appointment time passed and he still wasn’t there, Miss Donna said to her, “Let’s just get it done.” By the time he arrived, Mom had a new hairdresser. He was history. These days, Mesha cuts Mom’s hair. Mesha is the newest employee at the salon.

These days, Mesha cuts Mom’s hair. Mesha is the newest employee at the salon.  She’s only been there 8 years. (Rose, who did Rebecca’s manicure/pedicure, has been there 35.) Mom has a husband and wife housekeeping team, Keena and Dimitri. Keena is Mesha’s mother-in-law. May as well keep it all in the family!

She’s only been there 8 years. (Rose, who did Rebecca’s manicure/pedicure, has been there 35.) Mom has a husband and wife housekeeping team, Keena and Dimitri. Keena is Mesha’s mother-in-law. May as well keep it all in the family!